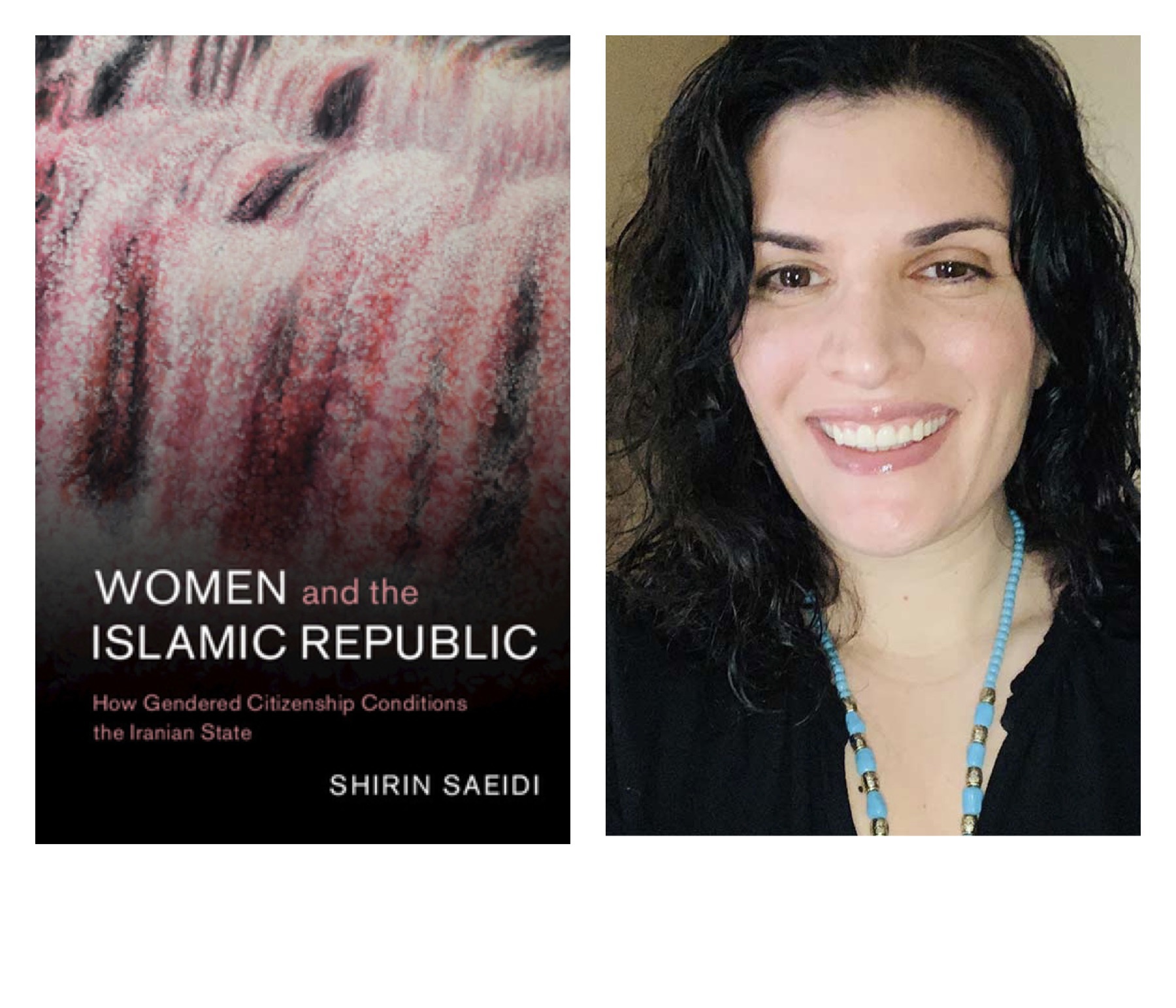

In a new book from Cambridge University Press, Women and the Islamic Republic: How Gendered Citizenship Conditions the Iranian State, author Shirin Saeidi explores the formation of women’s rights, roles and responsibilities in post-revolutionary Iran. While the newly formed Islamic Republic transformed Iranian society after 1979 and formulated a particular narrative of the Iranian citizen, ordinary Iranians employed their own agency as they negotiated, contested and accepted various aspects of the state’s account. Saeidi’s book is both a welcome addition to the growing canon of scholarship on post-revolutionary Iran and a revealing study on a topic often discussed but hardly understood: Iranian women.

What stands out in Saeidi’s study is her focus on non-elite Iranian women, especially from leftist or pious backgrounds. By acknowledging and emphasizing the importance of the actions of these women, Saeidi brings them out of obscurity and centers their stories within the larger project of state formation. Combining field research in Iran—with intimate stories from her interlocutors of different political leanings—with theories of citizenship and statecraft, and a command of previous scholarship, Saeidi presents a study that is at times personal, yet always careful to maintain its critical lens. Her own stories that appear at times in the book are a reminder of her time in Iran as a researcher and the experience of being an Iranian American challenging our own assumptions.

Not only does the author highlight an underrepresented group within the scholarship of modern Iran, but also an understudied period of contemporary Iranian history, the Iran-Iraq war (1980-88). Despite the significance of the war in Iran’s current affairs, its history as one of the bloodiest wars in recent decades, and its geopolitical impacts on the region, the Iran-Iraq war has not received enough research and attention. Though recent works such as Mateo Farzaneh’s in-depth study of Iranian Women and Gender in the Iran-Iraq War have helped to fill this gap, Saeidi’s book is another important contribution to our understanding of the war and how non-elite Iranian women negotiated the meaning of citizenship after the major upheavals of the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the war itself.

Saeidi looks at how Iranian women played an active role in the war effort, both in the warfront and at home taking on new roles, while pushing the boundaries of gender limitations and discriminations defined by the state. Saeidi argues that similar to Islamist women, leftist women were drawn to political movements and challenged traditional views of gender roles through their activism. Using poetry, close relationships, self-care and caring for others as archives of study, Saeidi shows how the idea of citizenship developed and evolved in unpredictable ways in the post-revolutionary Iranian state, underscoring the agency of Iranian women.

As Saeidi argues and her book illustrates, our understanding of citizenship, rights, and statecraft in Iran could be more illuminating when we remove the politicized approaches that view the Islamic Republic as a monolithic, fixed entity. Instead, reliable research that examines the transformations and fluid nature of the Islamic Republic’s state-building project can help expand our understanding of the Iranian state and how its citizens have challenged that project. Iranian women are not only subjects of the state but also its makers, despite the state’s authoritarianism. As the author aptly concludes: “Undoubtedly, in whatever direction Iran’s struggle for state formation goes, the Iranian nation has its female population to thank for fueling the struggle toward citizenship in the post-revolutionary era.”

Learn more about the book and get a copy here!

Back to top