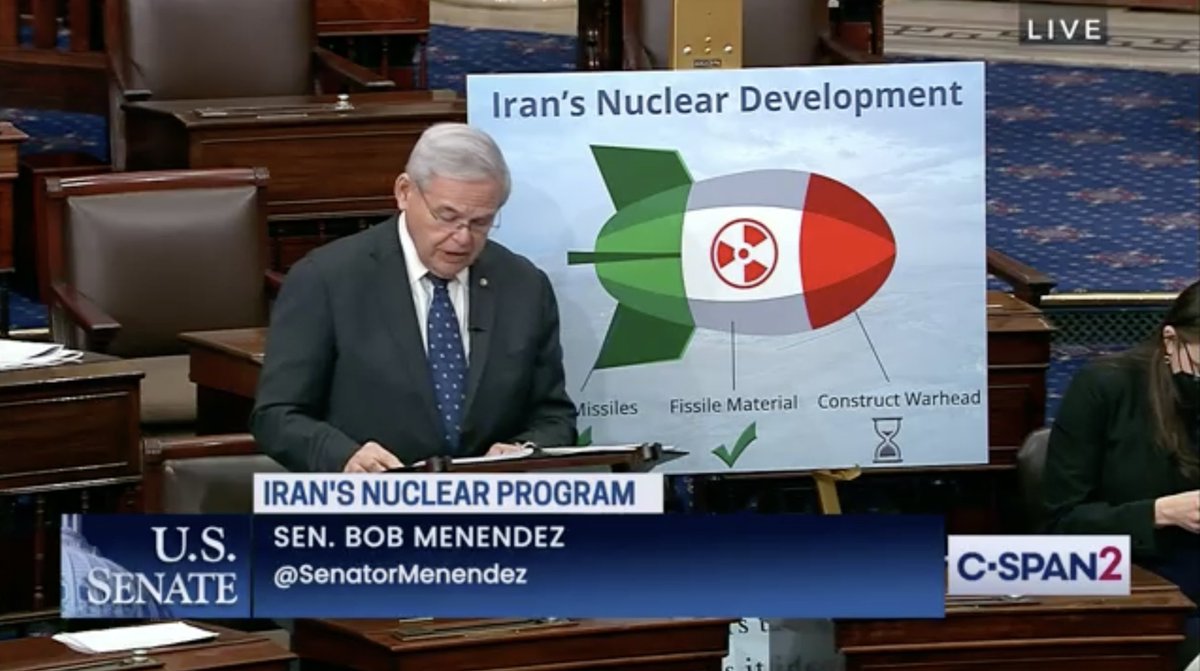

Late last week, Sens. Bob Menendez (D-NJ) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC) introduced a resolution pushing the Biden administration to adopt an alternative approach to Iran and its nuclear program. Menendez and Graham are long-time vocal critics of the nuclear agreement with Iran, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and have stepped up attacks on the Biden administration’s ongoing diplomatic efforts to revive the agreement.

S.Res. 511 would encourage the administration to provide nuclear fuel to Iran and other states in the Middle East from an international nuclear fuel bank on the stipulation that they forgo domestic uranium enrichment. It also seeks to clarify which U.S. sanctions could be on the table for a subsequent agreement with Iran and suggests that such an agreement should be considered as a treaty.

However, the proposal laid out in S.Res. 511 is far from a viable alternative to nuclear negotiations. It is a non-binding, unenforceable resolution that appears primarily designed as a ploy to give opponents of Iran diplomacy cover for future efforts to subvert diplomatic progress by claiming they support a mythical “better deal.” If this half-baked proposal were adopted by the Biden administration, it would pour fuel on the fire of a rapidly escalating nuclear crisis with Iran and force Biden to choose between war and Iran on the threshold of a nuclear weapon.

Upends Congressional Review

Under the bipartisan Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act (INARA), new nuclear agreements with Iran undergo a period of Congressional review. Under this process, Congress can halt implementation of an agreement if opponents obtain veto-proof support for an expedited resolution of disapproval in each chamber. In 2015, the JCPOA was implemented after Congress reviewed the agreement and supporters blocked resolutions of disapproval from moving to the President’s desk.

However, the Menendez-Graham resolution risks up-ending this bipartisan process by urging that “any international agreement limiting Iran’s nuclear program and providing sanctions relief” be submitted to the Senate as a treaty. If adopted, this would flip the review process on its head. Instead of two-thirds majorities in each chamber needed to disapprove of a nuclear agreement to block it from being implemented, the President would need to convince two-thirds of the Senate to support a nuclear agreement before it could be implemented. Such a bar is unlikely to ever be cleared, as Republicans have united to kill a variety of seemingly-unobjectionable proposals over the years – from the UN Rights on Disabilities Treaty pushed by Bob Dole to an official commission investigating the January 6th attack on the Capitol.

Writing as Vice President in 2015, Joe Biden himself noted the long history of American Presidents concluding diplomatic agreements without the affirmative approval of Congress, following the infamous Tom Cotton-led letter to Iran warning it against concluding an agreement with the United States. Biden said “Since the beginning of the Republic, Presidents have addressed sensitive and high-profile matters in negotiations that culminate in commitments, both binding and non-binding, that Congress does not approve. Under Presidents of both parties, such major shifts in American foreign policy as diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China, the resolution of the Iran hostage crisis, and the conclusion of the Vietnam War were all conducted without Congressional approval.”

It is unclear why the Menendez-Graham resolution endorses the fringe treaty argument against the JCPOA, but Senators should be wary of its apparent attempt to up-end the bipartisan process for reviewing new nuclear agreements with Iran.

Doubles down on “zero enrichment” fantasy”

Menendez and Graham’s resolution encourages the U.S. to support the provision of nuclear fuel to Iran from an international fuel bank. Such an idea could be a part of future diplomatic efforts involving Iran, but Menendez and Graham tie it to a poison pill “zero enrichment” demand. Only by giving up all enrichment on Iranian soil can Iran secure nuclear fuel internationally.

The core reason the JCPOA became possible was not U.S. sanctions, but U.S. diplomatic flexibility. The zero enrichment policy was pursued by the U.S. government throughout the George W. Bush administration, but it led to a dramatic expansion of Iran’s nuclear program, as Iran went from a little over one hundred centrifuges in 2003 to 19,000 by 2013. Only by offering limited Iranian enrichment via backchannel negotiations did the Obama administration secure serious buy-in for a diplomatic agreement that led to both the Joint Plan of Action (JPOA) in 2013 and JCPOA in 2015. The Trump administration adopted a similar zero enrichment line, and only succeeded in spurring Iran’s nuclear program to new heights.

Pursuing such a failed strategy again would have profound consequences. Iran is enriching uranium at 60% and bringing online advanced centrifuges that have cut the time it would take to produce sufficient fissile material for a nuclear weapon, if it made the political decision to do so. Threatening Iran into giving up its enrichment won’t work, and may push Iran to cross U.S. or Israeli red lines.

A sanctions offer designed to be rejected

Menendez and Graham’s resolution does support sanctions relief beyond the scope of the JCPOA, suggesting that U.S. primary sanctions could be exchanged in order to secure Iran surrendering its domestic enrichment capabilities. However, it indicates that sanctions nominally tied to Iran’s non-nuclear activities – including regional actions, support for designated terrorist groups and hostage taking – continue to be enforced.

In so doing, the resolution fails to grapple with the fact that the Trump administration effectively moved the goalposts on sanctions relief in order to tie Biden’s hands and obstruct a restoration of the JCPOA. Iran’s financial and oil sectors, which formed the core of sanctions relief under the JCPOA, are now designated not just under nuclear-related authorities but under terrorism-related authorities. Unless and until these sanctions are lifted in totality and sanctions relief is effectuated, Iran will not agree to rejoin the JCPOA or enter a new deal.

Similarly, it is unclear how much the carrot of primary sanctions relief would entice Iran to sign up for more expansive nuclear concessions. Opinion polling indicates majorities in Iran distrust U.S. sanctions relief, oppose new concessions and don’t expect the U.S. to uphold its obligations under the agreement. These positions are reflected in Iran’s political elite, with conservatives dominating all decision-making bodies in the government.

Not an alternative to a strong deal

It is generally worth exploring new ideas on how to engage Iran diplomatically. Unfortunately, the Menendez-Graham resolution doubles down on the failed approach of the Trump administration in demanding more from Iran with less diplomatic credibility. It is an offer designed to be rejected to ratchet up tensions further. Sen. Menendez, in a floor speech earlier this month, suggested that new pressure and overt threats of military force against Iran might intimidate Iran into bowing to such an idea. But this ignores everything we have learned about Iran’s response to pressure, which is always met with an equal and opposite reaction. President Biden needs to resolve the nuclear crisis with Iran, not inflame it. Senators would be wise to ignore this proposal as nothing more than a half-baked attempt to divert Biden from a successful restoration of the JCPOA, which would be strongly within U.S. interests.

Back to top